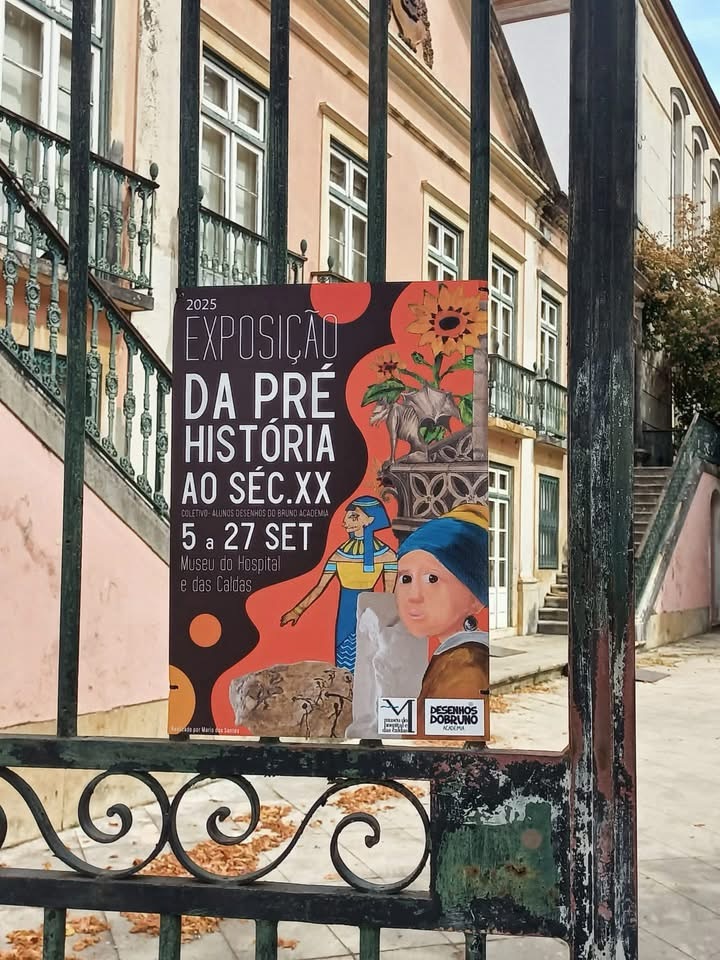

The collective exhibition “From Pre-History to the 20th Century”, carried out by the students of Drawings do Bruno Academia during the 2024/25 academic year, invites the public to an artistic journey through time. The exhibition covers different periods in the History of Art, recreating techniques and styles that have marked human expression over the centuries.

From the first records of visual communication, present in cave paintings, through the fascination of Ancient Egypt, with the creation of false papyrus, to the elegance of Greek sculpture in plaster, each work evokes the essence of an era. The route continues with the verticality and mystery of the Gothic period, translated into Chinese ink drawings of cathedrals and gargoyles. It progresses with the Renaissance masters, with oil painting on canvas, and culminates in the aesthetic revolutions of modernity: Impressionism, Naturalism and culminating in an introduction to Cubism, represented in oil pastel.

More than an exhibition, this is an exercise in discovery, experimentation and dialogue between past and present, in which each student (between the ages of 7 and 19) becomes an active part of humanity’s long artistic tradition.

PRÉ-HISTORY

Prehistory (40,000 to 5,000 years B.C.)

Inspired by the first artistic records of humanity, the students painted stones with natural pigments – curry, beetroot, pepper, saffron, blackberries, coffee, blueberries, among others. Like our ancestors, they recreated hunting scenes, exploring man’s connection with nature and his need to communicate through images.

Cave painting emerged in Prehistory, especially in the Upper Paleolithic, around 40,000 BC. Prehistoric men used natural pigments, such as charcoal, iron oxides, blood, animal fat and clay, applied with their fingers, rudimentary brushes or even blown through hollow bones.

The most common themes were animals (bison, horses, deer) and hunting scenes, portrayed with great realism and movement. Symbols and simplified human figures also emerged. The paintings had magical, religious or communication functions, such as rituals to ensure success in hunting.

In Portugal, we have one of the largest sets of outdoor Rock Art in Vale do Côa (Vila Nova de Foz Côa) which is a UNESCO World Heritage Site and in Escoural (Évora).

ANCIENT EGYPT (3,000 BC)

The students made their own “papyrus” from paper, coffee and white glue. On it, they illustrated figures obeying the law of frontality and the rigid style characteristic of Ancient Egypt, reflecting the importance of order and symbolism in this civilization.

Egyptian painting emerged around 3,000 BC and was done in tombs, temples and palaces. The main themes were essentially about the glorification of the gods and pharaohs, rituals and everyday life.

The figures were stylized, with important people larger and without perspective (head in profile, frontal torso and legs seen from the side – Law of Frontality – always with the aim of portraying life beyond death

The colors had symbolic meanings (green = life, black = death, red = power, blue = sky). The function was religious, funerary and decorative, helping in the afterlife.

CLASSIC PERIOD (480–323 BC)

Inspired by Ancient Greece, the students drew figures based on classical sculptures and brought the shapes to life through the plaster subtraction technique. The result are pieces that evoke the ideal of beauty, balance and harmony that has deeply marked Western culture. This module preceded a visit to the studio of the Caldensian sculptor, Carlos Oliveira in Salir de Matos.

Sculpture from the Classical Period of Ancient Greece stands out for its balance, harmony and proportion, reflecting the Greek search for perfection of the human body.

Sculptors worked mainly with marble, bronze and wood, creating figures of gods, heroes and athletes. The works showed the idealized human body, with mathematically balanced proportions, expressing serenity and controlled movement through the technique known as “Contraposto”. Anatomical details were precise and naturalistic, and suggested movement remained elegant and without dramatic exaggeration. These sculptures had religious, commemorative and decorative functions, being used in temples, squares and to celebrate heroes and victorious athletes.

In Portugal, Roman statues and busts found in places such as Conímbriga, Milreu and Braga stand out, representing gods, emperors and important citizens.

MEDIEVAL PERIOD (11th-15th centuries)

Using Indian ink on craft paper, the students immersed themselves in the dark atmosphere of the Middle Ages. They depicted Romanesque buildings, Gothic cathedrals, and gargoyles, even letting their imaginations run wild to create original gargoyles that never existed, blending history and fantasy.

Medieval sculpture developed primarily in the Romanesque (11th-12th centuries) and Gothic (13th-15th centuries) styles, and was strongly linked to religious architecture. In Romanesque, rigid, frontal figures with unrealistic proportions predominated, representing saints, animals, and biblical scenes, often in reliefs on churches and portals. In Gothic, sculptures became more naturalistic and elongated, with greater expressiveness, anatomical details, and representation of movement, visible in cathedrals and cloisters.

In Portugal, the Batalha Monastery is the most representative example of Portuguese Gothic, with portals, cloisters, and chapels richly decorated with detailed sculptures of saints, religious figures, and ornamental motifs, reflecting the late Gothic period. The Convent of Christ in Tomar demonstrates the transition from Romanesque to Gothic, not to mention the Monastery of Alcobaça and Santarém, considered the capital of Gothic in Portugal. Although later, in the Church of Nossa Senhora do Pópulo, we can observe some gargoyles that sparked so much interest among the students.

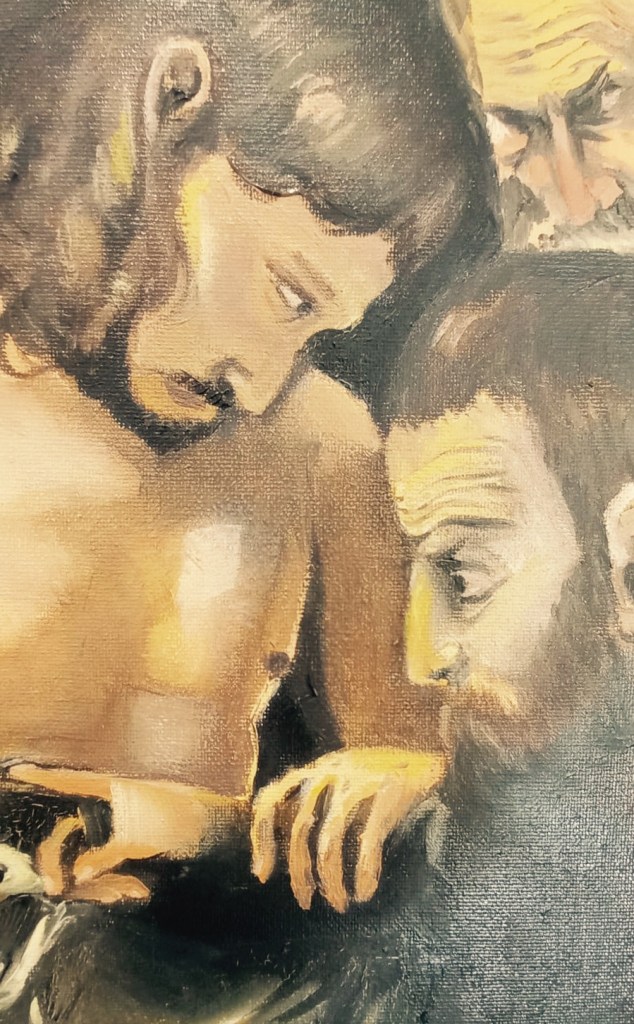

RENAISSANCE (15th-16th centuries)

Using the grid technique, each student reproduced works by great Renaissance masters in oil on canvas. The exercise allowed students to understand the search for proportion, realism, and the idealized representation of the human figure, symbols of this era of cultural rediscovery.

Renaissance painting, developed in Europe between the 15th and 16th centuries, was distinguished by its return to classical antiquity, realism, perspective, and the study of human anatomy.

Artists sought to represent space and the human body in a more natural way, using techniques such as linear perspective, chiaroscuro (light and shadow), and more realistic colors.

The topics included religious, mythological, and portraiture, reflecting both faith and an interest in humanity and the natural world.

In Portugal, the Renaissance manifested itself mainly in panels in churches and palaces, with notable examples such as the Main Chapel of the Church of São Vicente de Fora and the panels of the Monastery of Jesus in Setúbal, which show Italian and Flemish influences in the representation of figures and scenes.

IMPRESSIONISM

Using oil pastels, students experimented with the technique of short, fragmented brushstrokes, recreating works by Impressionist masters. Color and light became the protagonists, capturing fleeting moments and the vibrancy of the atmosphere using oil pastels on 200g Canson paper.

It emerged in France in the second half of the 19th century, marked by plein air painting and the pursuit of capturing light and its variations. Impressionists such as Monet, Renoir, and Degas favored quick brushstrokes and pure colors to convey the immediate sensation of a moment. Breaking with academic tradition, they depicted everyday scenes, landscapes, and fleeting moments, emphasizing visual impressions.

In Portugal, José Malhoa, Columbano Bordalo Pinheiro, Silva Porto, and Marques Silva gave face to this movement. They represented realism with naturalist and impressionist influences, connecting national art with international trends. The movement thus established itself as a celebration of Portuguese reality, without idealizations, but with great social and cultural sensitivity.

NATURALISM

The students explored oil pastels to create works of their own choosing, inspired by close observation of nature and everyday life. Each work reveals the artist’s individual perspective, in tune with the spirit of the Naturalist movement.

In Naturalism, the painter depicted everyday scenes with great attention to detail, light, and color, valuing direct observation of nature and real life. He aimed to portray human beings without idealization, often highlighting dark or “problematic” aspects of society.

CUBISM

The students were introduced to Cubism, creating original compositions based on the geometrical representation of forms. Space, objects, and figures were fragmented and reorganized, showing new perspectives on a single plane. They used oil pastels, watercolors, and markers on 200g paper.

Cubism emerged in Paris in the early 20th century with Picasso and Braque, revolutionizing painting. Instead of traditional perspective, the artists fragmented objects and figures into geometric shapes, showing multiple points of view simultaneously. This innovative visual language paved the way for abstract art and marked a decisive break with the classical representation of reality.

In Portugal, it gained expression from the 1910s onward, integrated into the modern avant-garde. Artists such as Amadeo de Souza-Cardoso, Eduardo Viana, and Almada Negreiros explored the fragmentation of forms, geometrical representation, and innovative use of color, adapting the Cubist language to the Portuguese context.

“MANUEL DOS SANTOS – THE HERO OF THE ARENAS”

Illustrations by Maria Luisa Maia

The 20 illustrations presented here are by Maria Luísa Maia, done in watercolor on 200g Canson paper, and bring to life the children’s book “Manuel dos Santos – The Hero of the Arenas,” written by her sister, Guadalupe Maia.

The project is the result of a family collaboration that combines words and images to tell the life story of Maria Luísa’s great-grandfather, the famous bullfighter Manuel dos Santos. Through soft and expressive colors, Maria Luísa recreates scenes that traverse memory, affection, and tradition, transporting the reader to the world of bullfighting and the human dimension of a major figure in Portuguese popular culture of the 1950s.

More than illustrations, these works are an artistic and emotional testament, in which the contemporary perspective of a young artist, just 9 years old, engages with family heritage and the preservation of collective memory.

WHO WAS MANUEL DOS SANTOS?

Born in Golegã, Manuel dos Santos stood out as one of the most notable Portuguese bullfighters, achieving enormous popularity in the 1940s and 1950s. His technical mastery, elegance, and courage made him a reference in bullfighting on foot, projecting Portugal’s reputation worldwide. He is remembered as an artist who elevated national bullfighting, influencing generations of bullfighters and remaining a symbol of Portuguese bullfighting tradition.

To learn more about Manuel dos Santos, simply go to Golegã and visit the museum opened this year to commemorate his centenary. You can also see the statue in his memory in the main square, designed by Amable Diego.

Visit us in